While there is active research for more effective disease-modifying drugs* the lack of any significant breakthroughs in the treatment of the Alzheimer’s disease has propelled a paradigm shift away from focusing solely on a drug solution, to an inclusive prevention model that emphasizes risk reduction and prevention, which promises to attenuate the portentous global burden incurred by the disease.

Current prevalence estimates (2016) for late-onset Alzheimer’s disease (LOAD) in the United States (U.S.) is approximately 5.1 million.(1) By 2050 the projected prevalence of LOAD is expected to escalate to 13.8 million and a staggering 106.8 million worldwide.(2,3) Pharmacological treatments for LOAD such as cholinesterase inhibitors and NMDA receptor antagonists may slow its progression or attenuate specific molecular pathomechanisms associated with the disease process, but are not long term solutions or curative.

Several clinical trials have recently explored the potential role of prevention-based interventions for decreasing the risk of late-onset Alzheimer’s disease (LOAD) and vascular dementia. The outcomes are encouraging. Multi-dimensional interventional strategies (implementing multiple treatment and prevention modalities simultaneously) versus mono-therapy (employing only with a single treatment modality e.g. drugs) has yielded promising results in reducing the eventual onset of dementia for aging individuals considered to be at higher risk.

These trials highlight the potential effectiveness of preventive approaches for individuals deemed to have a higher risk for vascular dementia and LOAD and for the management of Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI).**

Mild Cognitive Impairment

The construct of MCI is now recognized as the transitional stage of brain degeneration that leads to LOAD and dementias associated with several other neurological and systemic diseases. The classification of MCI subtypes (amnestic MCI and non-amnestic MCI subtypes)*** may serve to predict the probability of conversion to LOAD, or the type of dementia that an individual diagnosed with MCI is at risk for.

Several studies indicate a higher conversion for amnestic MCI to LOAD. (4) The greater the memory loss, the more severe the impairment may be, and the higher the risk for progressing to LOAD. For a more detailed overview of the classifications of MCI, please read: “Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI)–Telltale Signs That You May Be At Increased Risk for Dementia or Alzheimer’s Disease”.

Early assessment of an individual’s apparent cognitive decline in the potential pathological continuum of MCI to LOAD conversion would present a priceless opportunity whereby interventions may delay progression or prevent the eventual dismal diagnosis of dementia. Genetic profiling would add additional insights.

ApoE4 genotypes are not only at higher risk for LOAD, carriers of the variant are at higher risk of MCI conversion from a prodromal pre-dementia stage (amnestic-MCI), to LOAD.(5)

Recent advances in the utilization of biomarkers **** and neuroimaging studies add to the growing tool bag of diagnostics that may provide invaluable insights for implementing risk reduction programs.

To date, clinical trials that attempted disease-modifying interventions with drugs have not demonstrated any significant amelioration of Alzheimer’s dementia. Why? It amounts to the proverbial too little, too late.

While mono-therapy drug trials investigating the effect of disease-modifying therapy on the progression of LOAD have not demonstrated any benefit to date, a more robust intervention scheme and earlier prevention strategies are showing promise of slowing cognitive decline and preventing the progression to dementia.

To that end, clinical trials investigating the potential role of nutrition, exercise, social activities and cognitive training in the preservation of cognitive function are either underway, or have recently concluded.(2)

For the sake of brevity and to highlight the multifactorial nature of multi-domain intervention approaches, I will describe three trials that have taken the route of a prevention strategy synergism that includes lifestyle and nutrition, and diet–the core elements to disease-modifying strategies associated with aging.

In addition, biomarkers were utilized to assess the modifiable factors associated with risk and progression of the disease process.

The utilization of genetic, biochemical, molecular and neuroimaging biomarkers are currently utilized in the early assessment of vascular dementia and LOAD before the diagnosis of frank dementia.

This integrated early evaluation process of an individual’s risk for late-onset Alzheimer’s disease or vascular dementia are top tier prevention approaches and central to any any disease-modifying strategy. The consensus for that model in dementia prevention is fortunately mounting.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain

Dementia Prevention Trials

Three large European multi-domain prevention trials, preDIVA, FINGER, and MAPT, have been launched with the goal of assessing the efficacy of multi-domain interventions in the prevention of cognitive decline, vascular dementia and late-onset Alzheimer’s disease in older adults with varying risk profiles.

FINGER

The Finnish Geriatric Intervention Study to Prevent Cognitive Impairment and Disability (FINGER), a two-year multi-center randomized controlled trial (RCT), was designed “to assess a multidomain approach to prevent cognitive decline in at-risk elderly people from the general population.”(6)

1260 adults of age 60-77 years were inducted based on their increased risk of dementia but not those with established dementia or more severe cognitive impairment based on their CAIDE Dementia Risk Score (Cardiovascular Risk Factors, Aging, and Incidence of Dementia).*****

The study participants were divided into two groups: An intervention group which was subjected to multi-domain intervention strategy and a control group.

The control group received only general health advice but none of the other intervention modalities. The multi-domain interventions included social activity, nutritional support, cognitive training, monitoring of metabolic and vascular risk factors and exercise.

The FINGER trial was finalized in 2014 and results showed 25% improvement in the Neuropsychological Test Battery (NTB) scores—a scale used to assess cognitive function in patients at increased risk of Alzheimer’s.

Moreover, the control group was found to be 31% more at risk of developing cognitive impairment in comparison to the intervention group.

To more adequately gauge the intervention strategies on vascular dementia and late-onset Alzheimer’s disease effect on dementia and AD incidence, a 7-year extended follow-up of the study was started in 2015. Biomarker and neuroimaging evaluations taken at the beginning and during the study at will be included the post-trial analysis.

MAPT

Another multi-domain clinical trial to take note of is the Multi-domain Alzheimer Preventive Trial (MAPT).(7) This French study included 1680 adults aged 70 years and over that showed initial symptoms of memory impairment and cognitive decline, but were not diagnosed cases of dementia or Alzheimer’s.

About 20% of the 1680 adults eventually dropped out of the trial. In this 3-year study, participants were divided into four groups:

- the omega 3 fatty acid (DHA) supplementation group,

- the multi-domain intervention group,

- the omega 3 fatty acid (DHA) plus multi-domain intervention group, and

- the placebo group.

The multi-domain intervention group was offered nutritional support, exercise advice and cognitive training. Results of neuroimaging studies (MRI, PET) were incorporated into the data collection.

Fish oil gelcaps

The 3 year intervention completed in March 2014 and an extended 2 year follow-up, the MAPT Plus, was just completed in 2016.

Results were reported at the 8th Clinical Trials in Alzheimer’s Disease conference in Barcelona, Spain this past November (2016).

As of this writing (I2/2016) the results of the trial are not yet published. However, in a communication to Alzforum (Alzforum.org) by the authors of the trial, only the omega 3 fatty acid (DHA) plus multi-domain intervention group had a statistically significant improvement.******

The multi-domain intervention improved their scores over baseline but the results just missed statistical significance. The other two groups, placebo and the omega 3 fatty acid (DHA) supplementation group without multi-domain intervention declined.

Also notable was the improvement in brain glucose metabolism in the omega 3 fatty acid (DHA) plus multi-domain intervention group. The placebo group showed no change, and the other groups had slight improvements.

The role and significance of impaired glucose metabolism (glucose hypometabolism) as a critical risk factor in LOAD is extensively covered in my book: The Diabetic Brain in Alzheimer’s Disease.

For a more complete description of the preliminary results reported to Alzforum please visit their overview @ http://www.alzforum.org/news/conference-coverage/health-interventions-boost-cognition-do-they-delay-dementia.

preDIVA

Finally, another RCT focusing on the use of multi-dimension interventions is the Prevention of Dementia by Intensive Vascular Care (PreDIVA). As the trial title describes, the goal is to assess a multi-domain intervention approach to vascular care in the elderly and the desired endpoint of decreasing incident dementia*******.

The trial included 3533 non-demented adult patients (70-78 years old), but the majority of the group had ben assessed as having one more risk factors associated with cardiovascular disease risk. The attendant care focused on the treatment of diabetes, hypertension, elevated cholesterol, weight reduction, smoking cessation and active exercise.

Preliminary reports at the two year mark showed a twofold reduction of blood pressure in the intervention group versus the control group.

A 6-year follow-up will assess whether “nurse-led intensive vascular care in primary care decreases the incidence of dementia and reduces disability”.(8) Brain atrophy rates as monitored by MRI will be included the final report.

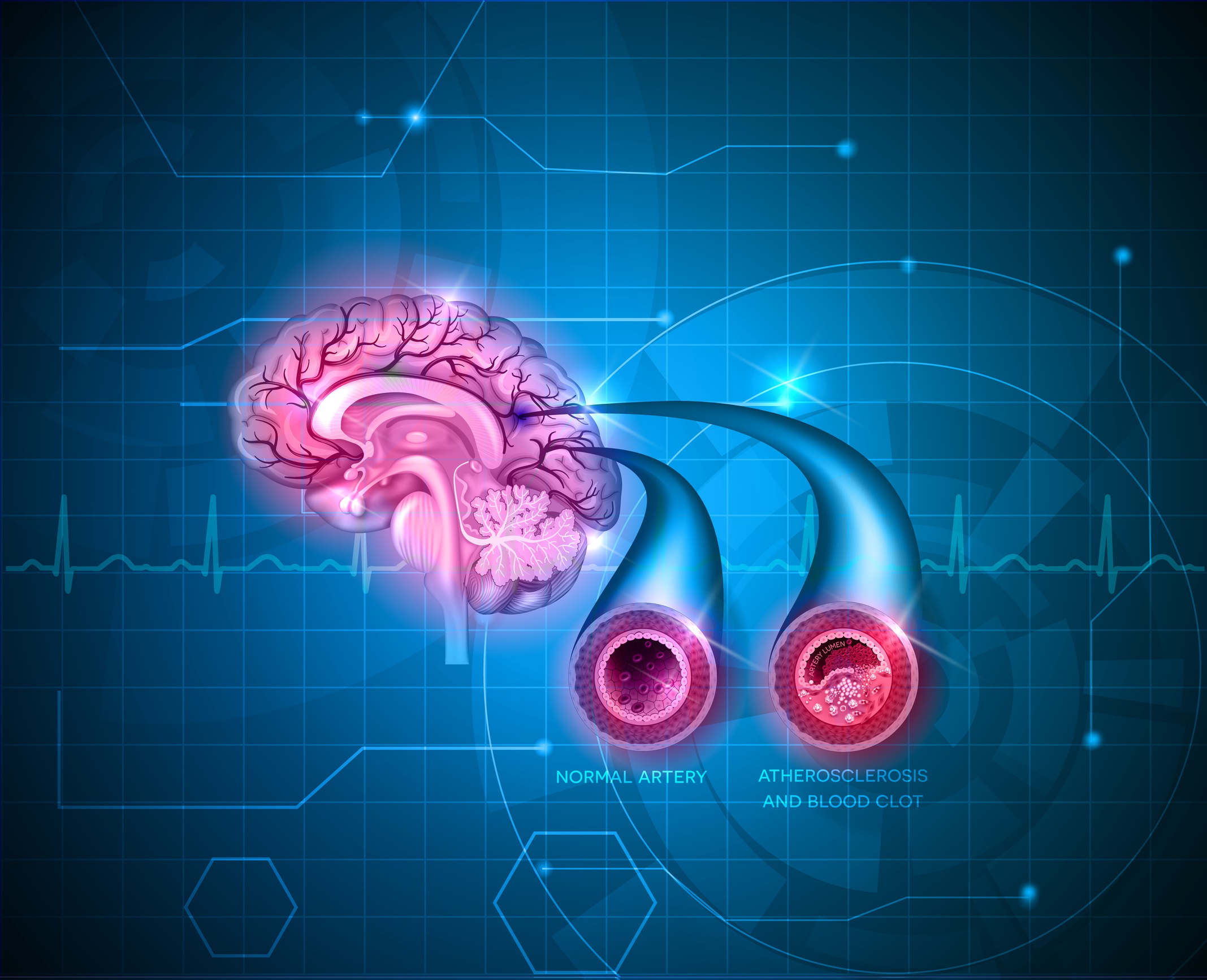

Coronary artery disease restricts blood flow to the brain and increases the risk for stroke, vascular dementia, and Alzheimer’s

These pioneering studies have laid the foundation for a more inspired approach towards multi-domain interventions that target dementia risk factors before the disease manifests in more severe cognitive decline and dementia.

A collaborative outgrowth from FINGER, MAPT and preDIVA has launched (2011) the European Dementia Prevention Initiative (EDPI). EDPI is spearheading an international consortium to implement a dementia prevention research model through the early assessment of cognitive impairment that may represent the pre-dementia phase of vascular dementia or Late-onset Alzheimer’s disease.

The launch of the EDPI has lead to another collaborative research project that will undertake the development of a novel online cardiovascular intervention platform. The Healthy Ageing Through Internet Counselling in the Elderly (HATICE) objective will include two primary goals:

- Develop an innovative, interactive internet intervention platform to optimize treatment of cardiovascular disease in the elderly

- Test this new intervention in a randomized controlled trial to investigate whether new cardiovascular disease and cognitive decline can be prevented

HATICE (www.hatice.eu) has recruited 4600 elderly individuals from three countries, Finland, France and the Netherlands, to participate in this landmark trial.

FINGER, MAPT, preDIVA and HATICE have taken inspired steps for the development of dementia prevention models. The results to date have demonstrated that the individuals in the intervention groups have stayed mentally sharper than controls that did not receive the intervention protocols. Such dementia prevention trials may possibly begin to offer hope in the mounting crisis that projected healthcare burden associated with Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia are expected to incur.

Here in the United States President Barack Obama signed into law the National Alzheimer’s Project Act (NAPA) in 2011. NAPA required the Secretary of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services to establish the National Alzheimer’s Project in 2012. “The National Plan to Address Alzheimer’s Disease” was instituted with the objective to both prevent and effectively treat Alzheimer’s disease by 2025. To that end, several U.S. trials have been initiated with the focus on preventive strategies.(9)

However, the trials currently in place or planned for here in the U.S. are drug trials and not multi-domain interventions. Why? The prevailing wisdom considers the current epidemiological evidence gathered from numerous trials linking heart disease, diabetes, nutrition, exercise and other lifestyle factors to dementia risk as insufficient for developing the types of multi-domain trials described above.

Critics point to flaws in the study design and the criteria for selecting the participants in multi-domain designed prevention trials. Yes, they are not perfect. The trial authors readily admit they are improvements to be made going forward but at least there is an effort that is building a foundation that will advance the prevention of vascular dementia and late-onset Alzheimer’s disease.

On the other hand, the focus of studies intent on the advancement of drug solutions is myopic.

Again, there is growing consensus and call to action for intervention strategies based on cardiometabolic risk factors that will yield enormous benefits to an aging population at risk for vascular and Alzheimer’s dementing disease.

To that very point, In 2009 “The Campaign to Prevent Alzheimer’s disease by 2020” (http://www.pad2020.org), proposed a multi-national collaboration for the “to accelerate innovation on detection and prevention for chronic brain disorders such as Alzheimer’s disease and dementia.” (10) PAD2020 warranted their proposal for such a collaborative action plan based on the “collective thinking of over 200 worldwide leaders in dementia research concur that a mission to prevent Alzheimer’s disease within a decade is an attainable scientific objective”.

Indeed, the future looks promising. All of the aforementioned multi-domain intervention dementia prevention trials and the enlightened call to action by the scientific community for disease modifying interventions will eventually serve as a model for research and future trials. While the European Dementia Prevention Initiative has taken that first critical step forward for interventions that will serve to reduce the risk of cognitive decline in the elderly the next logical step is to initiate a scope of intervention trials in a much younger population.

The risk for dementia is set in motion by a host of genetic and environmental risk factors that are prominent at mid-life. The neuropathology of vascular dementia and late-onset Alzheimer’s disease begins years and perhaps decades before a more prominent disease process is noticeable or before it is diagnosed, and cardiometabolic risk factors are center stage to in the timeline of the disease process.

For a more detailed overview on the biological links between type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease to late-onset Alzheimer’s disease, please read my book: The Diabetic Brain in Alzheimer’s Disease. It is a work this author has put forth as an awareness-building call to action for all those individuals that may run the risk of vascular dementia and LOAD, and the proactive steps that can be instituted for prevention.

Footnotes

* Drugs designed to modify specific pathomechanisms associated with the development of Alzheimer’s disease

** The medical diagnosis of Mild Cognitive Impairment represents abnormal cognitive decline that reflects degenerative brain processes that is beyond normal aging and may precede more severe neurodegenerative processes and the diagnosis of dementia.

*** MCI includes two basic subtypes: 1. amnestic MCI and 2. non-amnestic MCI.

Additional subtypes under these classification include:

- amnestic MCI-multiple cognitive domain

and

- non-amnestic MCI-single cognitive domain and, non-amnestic MCI-multiple cognitive domain

**** Biomarkers: In medicine, a measurable and quantifiable biological parameters that serve as indices of health or a disease process

e.g., specific enzyme concentration, specific hormone concentration, specific gene phenotype distribution in a population, presence of biological substances that serve as indices for health and physiology related assessments such as disease risk, psychiatric disorders, environmental exposure and its effects, disease diagnosis, metabolic processes, substance abuse, pregnancy, cell line development, epidemiologic studies, etc.

Source: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/mesh/68015415

***** The CAIDE Risk Score assessment tool by Merz Pharmaceuticals is available as an APP on iTunes. The App is validated by several studies.(11)

CAIDE began in 1998 and is an ongoing joint effort of the Department of Neurology, University of Finland, Kuopio Campus; the National Institute of Health and Welfare, Helsinki, Finland; and ARC. Its purpose is to investigate the connection between social, lifestyle, and cardiovascular risk factors and cognition, dementia, and structural changes in the brain.

****** Conflicts of interest: MAPT study was partially funded by the Institut de Recherche Pierre Fabre, Exhonit Therapeutics and Avid Radiopharmaceuticals Inc

******* The term: “Incident dementia” represent the statistics that represents newly diagnosed patients in a given timeframe.

References:

1. 2015 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures

Alzheimer’s Association

Alzheimer’s & Dementia Volume 11, Issue 3, March 2015, Pages 332–384

2. Alzheimer disease in the United States (2010–2050) estimated using the 2010 census

Liesi E. Hebert, ScD,corresponding author Jennifer Weuve, ScD, Paul A. Scherr, PhD, ScD, and Denis A. Evans, MD

Neurology. 2013 May 7; 80(19): 1778–1783.

3. FORECASTING THE GLOBAL BURDEN OF ALZHEIMER’S DISEASE

Ron Brookmeyer, Elizabeth Johnson, Kathryn Ziegler-Graham, and H. Michael Arrighi

Johns Hopkins University, Dept. of Biostatistics Working Papers

Year 2007, Paper 130

4. Importance of Subtle Amnestic and Nonamnestic Deficits in Mild Cognitive Impairment: Prognosis and Conversion to Dementia

S.D. Rountree, S.C. Waring, W.C. Chan, P.J. Lupob, E.J. Darby, R.S. Doody

Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 2007;24:476-482

5. The Apolipoprotein E4 allele and incident Alzheimer’s disease in persons with mild cognitive impairment.

Aggarwal NT, Wilson RS, Bienias JL, Berry-Kravis E, Bennett DA.

Neurocase 2005;11:3-7

6. A 2 year multidomain intervention of diet, exercise, cognitive training, and vascular risk monitoring versus control to prevent cognitive decline in at-risk elderly people (FINGER): a randomised controlled trial

Ngandu, Tiia et al.

The Lancet , Volume 385 , Issue 9984 , 2255 – 2263

7. Omega-3 Fatty Acids and/or Multi-domain Intervention in the Prevention of Age-related Cognitive Decline (MAPT)

Vellas1, I. Carrie1, S. Gillette-Guyonnet, J. Touchon, et al.

The Journal of Prevention of Alzheimer’s Disease – JPAD© Volume 1, Number 1, 2014

8. Prevention of Dementia by Intensive Vascular Care (PreDIVA): A Cluster-randomized Trial in Progress

Edo Richard, Esther Van den Heuvel, Eric P. Moll van Charante, Lenny Achthoven, Marinus Vermeulen, Patrick J. Bindels and Willem A. Van Gool

Alzheimer Disease & Associated Disorders. September 2009. vol. 23 no. 3 198-204

9. Obstacles And Opportunities In Alzheimer’s Clinical Trial Recruitment

Jennifer L. Watson, Laurie Ryan, Nina Silverberg, Vicky Cahan, and Marie A. Bernard

Health Aff (Millwood). 2014 Apr; 33(4): 574–579.

10. Creating a transatlantic research enterprise for preventing Alzheimer’s disease.

Khachaturian ZS, Camí J, Andrieu S, et al.

Alzheimers Dement 2009;5:361-366.

11. The CAIDE Dementia Risk Score App: The development of an evidence-based mobile application to predict the risk of dementia Sindi, Shireen et al. Alzheimer’s & Dementia: Diagnosis, Assessment & Disease Monitoring , Volume 1 , Issue 3 , 328 – 333