Midlife may be a critical juncture in one’s life and a time for contemplating what the rest of it will look like. It may be a time of reflection on time well spent or sheer regret for not having done enough of what you really love to do. Midlife may also be a turning point in your risk for late-onset Alzheimer’s disease as the disease process may already be silently brewing in your brain.

Indeed, midlife may be time of crisis—the proverbial fork in the road for many of us.

While the emotional and spiritual grappling that comes with it may reveal a bigger purpose and a path forward, it often overlooks the vehicle to get you there—your body and brain.

In all likelihood, your health may be into its own hidden midlife crisis and that may be part of your challenge—although, how would you know?

All too often, we are not even aware that the integrity of our health is headed south. We may not feel that great, but we put off doing something about it as we have enough on our hands to worry about.

Instead we begin to throw little fixes at it such as over the counter stress and pain relief meds. Coffee and 5 hour energy drinks become a crutch.

If you have been to a physician, he is likely encouraging more fixes in the form of drug therapy for elevated cholesterol, high blood sugar, or other conditions.

Plus, the belly fat is a nagging reminder that you are not taking your diet and exercise as seriously as you should.

For both men and women, hormones are likely depleted or out of balance, and stress has taken its toll as well. It is not easy to muster a boundless enthusiasm for the next big chapter in your life when you feel depleted and out of sorts.

For women, the menopausal transition brings its own set of unique challenges. Declining estrogen levels at menopause bings into question how that can that affect your long-term health. Low estrogen in the menopausal transition is linked to a greater risk for Alzheimer’s in mid-to-late life.(1)

What to do? Well, do nothing and it is likely to get worse.

Undeniably, taking control of your health and what that means for rest of your life is important as what may be stirring underneath these midlife health issues for many individuals is a much bigger crisis that will come to bear later in life.

Worse, no one is giving you the heads up that all of these seemingly getting older issues are warning signs that the metabolic, hormonal, and biochemical undercurrents to these health problems could be the setup for cognitive problems or dementia as you age.

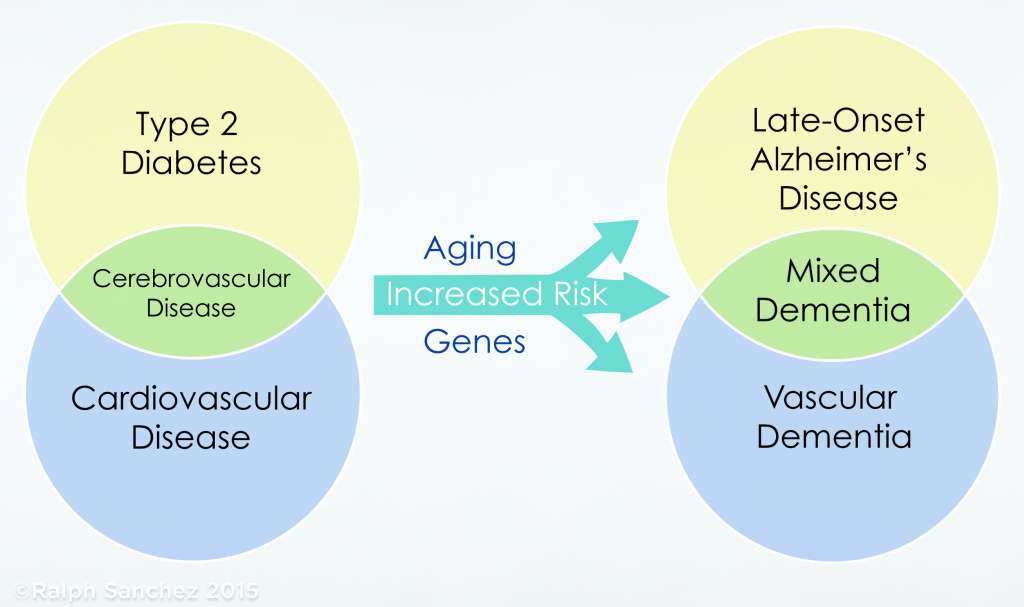

For example, the timeline for the onset and progression for late-onset Alzheimer’s disease (LOAD) can span 20 to 30 years or more, and the risk factors associated with cardiovascular and metabolic disease (cardiometabolic) that begins earlier in life significantly raises the risk for the onset of Alzheimer’s and dementia later in life.(2)

Fig. 3

From The Diabetic Brain in Alzheimer’s Disease

Chronic Inflammation

The undercurrents of chronic inflammation and oxidative stress associated with cardiometabolic disease is one of the core components to elevating the risk for vascular dementia and LOAD in aging.

A growing number of individuals are generally aware of the link between inflammation and various health disorders, but the concept that systemic inflammation is linked to common age-related diseases and a risk for cognitive impairment or dementia as they age…well that is just not the usual connection that most individuals think of when it comes to their health or how that all plays out 20 or 30 years down the road.

From The Diabetic Brain in Alzheimer’s Disease

From The Diabetic Brain in Alzheimer’s Disease

The role of systemic inflammation as a risk factor for Alzheimer’s and dementia has been heavily investigated. Adding to that body of evidence, a recent study investigated the link between midlife inflammation and the risk for cognitive impairment and concluded that people “with higher levels of inflammatory markers in midlife had steeper rates of cognitive decline over the next 20 years.”(3)

Another recently published study showed that people with elevations of inflammatory markers at midlife (fibrinogen, albumin, white blood cell count, von Willebrand factor, and Factor VIII) was linked to “smaller brain volumes in late life” (brain atrophy) than in study participants that did not have the elevated biomarkers of inflammation.(4)

For a deeper dive into the role of inflammation in Alzheimer’s disease, please read:

Inflammation and Alzheimer’s Disease—Cause, or Effect?

In addition, “Polyphenols in the Protection Against Cardiovascular Disease and Dementia“, is another read on the role of cardiovascular disease in the risk for late-onset Alzheimer’s disease and how nutrition and dietary patterns can greatly reduce that risk.

Alzheimer’s starts in the womb?

The risk for vascular disease, obesity, hypertension, and type 2 diabetes can begin in early childhood and may even begin in the womb under certain conditions.

Many studies have shown that the offspring of obese mothers have greater future risk of obesity, type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease.

A common complication in pregnancy, chronic fetal hypoxia (an adequate supply of oxygen) that is associated with maternal overweight and obesity, preeclampsia, and gestational diabetes can result in fetal growth restriction and the increased predisposition to metabolic syndrome, cardiovascular disease and other disorders in adult life.”(5)

Left untreated, the hypoxic prenatal environment raises the risk for hypertension and cardiovascular disease in adulthood and similar studies have demonstrated fetal brain damage from chronic fetal hypoxia (intrauterine hypoxia) and the “increased risk of neurodegenerative disorders in later life.”(6)

In studies using mice, chronic fetal hypoxia triggered the same pathological outcomes in the brain as evidenced with Alzheimer’s disease and included oxidative stress, neuroinflammation, increased processing of amyloid protein, and loss of brain tissue (brain atrophy). Antioxidant therapies and polyphenols greatly reduced the adverse outcomes associated with fetal hypoxia.(6,7,8,9)

Not surprisingly, studies centered on the protection against brain ischemia (restriction in blood supply) in adults have demonstrated that a host of nutrients including antioxidants and polyphenols were protective against the damage from silent brain infarcts and lesions that are common in healthy elderly people.

Gestational factors related to fetal hypoxia and additional prenatal conditions of malnutrition, infections, and stress are now viewed as epigenetic triggers that can significantly raise the risk of neurodegenerative disease later in life.(10)

These gestational complications that are linked to a more vulnerable brain and the onset of Alzheimer’s disease and dementia later in life are not hard to fathom.

All of the maternal risk factors that are linked to chronic fetal hypoxia—diabetes, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, and smoking, are prime risk factors for impaired blood flow to the brain and the heightened risk for vascular dementia and Alzheimer’s disease throughout an individuals lifespan. It may start at birth or later in life, but it grows into a risk for Alzheimer’s that morphs into a midlife crisis that is largely unnoticed or undiagnosed.

For example, according to the Centers for Disease Control, more than one out of three American adults have prediabetes. That adds up to 84 million Americans with prediabetes, and 90 percent are not aware that they have this undercurrent of metabolic disease that will likely progress to type 2 diabetes.

Do you have prediabetes? It is vital to know if you are on the threshold of crossing over into type 2 diabetes. Take the prediabetes test here.

In addition, in the U.S. approximately 9 percent of the population are type 2 diabetics (both diagnosed and undiagnosed) and about 24 percent of those are unaware of their condition.(11)

Midlife cardiovascular risk factors (e.g.,T2D, hypertension) vastly increase the likelihood for developing vascular dementia and Alzheimer’s disease, as one ages.(12,13)

Type 2 diabetes (T2D) increases the risk for late-onset Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia by 50 percent, or more, compared with those without T2D.(14)

To the point, the research over the last few years increasingly emphasizes the mantra I repeat often in my book, The Diabetic Brain in Alzheimer’s Disease, midlife cardiometabolic disease is highly predictive for the risk and onset of dementia and Alzheimer’s as you age.

Your next steps? Get help with a thorough evaluation of your risk factors that may be silently putting your brain at risk for cognitive impairment as you age. To make sure you are on the right track, the BrainDefend™ Body-Brain Renewal Program is designed to do just that for you.

References

1. Estrogen Regulation of Mitochondrial Bioenergetics: Implications for Prevention of Alzheimer’s Disease

Jia Yao and Roberta Diaz Brinton

Adv Pharmacol. 2012 ; 64: 327–371.

2. Is late-onset Alzheimer’s disease really a disease of midlife?

Karen Ritchiea, Craig W. Ritchiec, Kristine Yaffee, Ingmar Skoog, Nikolaos Scarmeas

Alzheimer’s & Dementia: Translational Research & Clinical Interventions 1 (2015) 122-130

3. Systemic inflammation during midlife and cognitive change over 20 years: The ARIC Study.

Walker K, Gottesman RF, Wu A, et al.

Neurology 2019; Epub 2019 Feb 13.

4. Midlife systemic inflammatory markers are associated with late-life brain volume-The ARIC study

Keenan A. Walker, Ron C. Hoogeveen, Aaron R. Folsom, Christie M. Ballantyne, David S. Knopman, B. Gwen Windham, Clifford R. Jack, Rebecca F. Gottesman

Neurology Nov 2017, 89 (22) 2262-2270

5. Cardiovascular Programming During and After Diabetic Pregnancy: Role of Placental Dysfunction and IUGR

Immaculate M. Langmia, Kristin Kraker, Sara E. Weiss, Nadine Haase, Till Schutte, Florian Herse and Ralf Dechend

Front. Endocrinol., 09 April 2019

6. Role of Prenatal Hypoxia in Brain Development, Cognitive Functions, and Neurodegeneration.

Nalivaeva NN, Turner AJ, Zhuravin IA.

Front Neurosci. 2018;12:825.

Published 2018 Nov 19.

7. Intervention against hypertension in the next generation programmed by developmental hypoxia.

Brain KL, Allison BJ, Niu Y, Cross CM, Itani N, Kane AD, et al.

PLoS Biol 2019, 17(1):e2006552

8. Placental Adaptation to Early-Onset Hypoxic Pregnancy and Mitochondria-Targeted Antioxidant Therapy in a Rodent

Nuzzo AM, Camm EJ, Sferruzzi-Perri AN, et al.

Model. Am J Pathol. 2018;188(12):2704–2716.

9. Chronic fetal hypoxia produces selective brain injury associated with altered nitric oxide synthases.

Dong Y, Yu Z, Sun Y, et al.

Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;204(3):254.e16–254.e2.54E28. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2010.11.032

10. Fetal programming of the human brain: is there a link with insurgence of neurodegenerative disorders in adulthood?

Faa G, Marcialis MA, Ravarino A, Piras M, Pintus MC, Fanos V.

Curr Med Chem. 2014;21(33):3854-76.

11. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National diabetes factsheet: national estimates and general information on diabetes and prediabetes in the United States, 2011 Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2011.

12. Increased risk of type 2 diabetes in Alzheimer disease

Janson J, Laedtke T, Parisi JE, O’Brien P, Petersen RC, Butler PC Diabetes. 2004 Feb; 53(2):474-81.

13. Type 2 Diabetes as a Risk Factor for Dementia in Women Compared With Men: A Pooled Analysis of 2.3 Million People Comprising More Than 100,000 Cases of Dementia

Saion Chatterjee, et al.

Diabetes Care 2016 Feb; 39(2): 300-307.

14. Vascular risk factors, cognitive decline, and dementia

E Duron and Olivier Hanon

Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2008 Apr; 4(2): 363–381.